I have long argued the aircraft carrier is an obsolete relic of a bygone era. In so doing, I have been subjected to mocking ridicule by many, and simply disbelieved by most. Only a mere handful of respondents to my carrier-disparaging public statements has concurred with my analysis of the issue.

Herein I present a formal defense of the proposition.

I submit that, in the context of a great power war, the aircraft carrier was effectively proven obsolete in 1945.

As a preface to my argument, I submit a brief history of the aircraft carrier, and the manner in which it abruptly burst upon the annals of military history in 1941.

That year saw first the British, then the Japanese, decisively prove what the aircraft carrier’s enthusiastic promoters had zealously preached for over a decade previous: that the age of the battleship was over; the aircraft carrier would be the new queen of the seas.

The battleship admirals were, unsurprisingly, dubious of the idea of naval aviation being useful for much more than reconnaissance for their big guns.

Nevertheless, to the credit of the persuasiveness of the aircraft carrier proponents, the navies of Great Britain, Japan, and the United States had, by 1941, produced several relatively mature specimens of ships not all that dissimilar to the carriers of today.

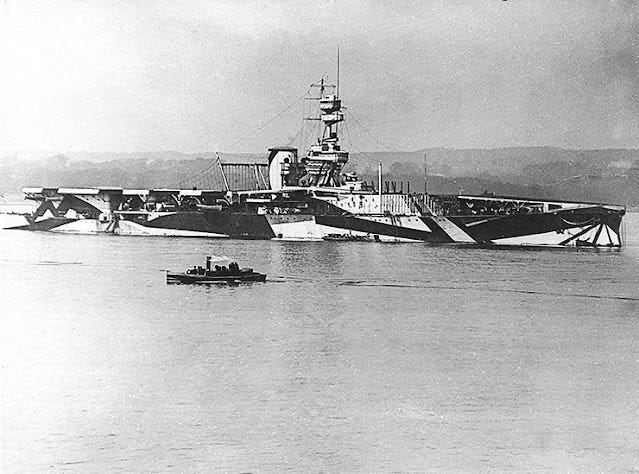

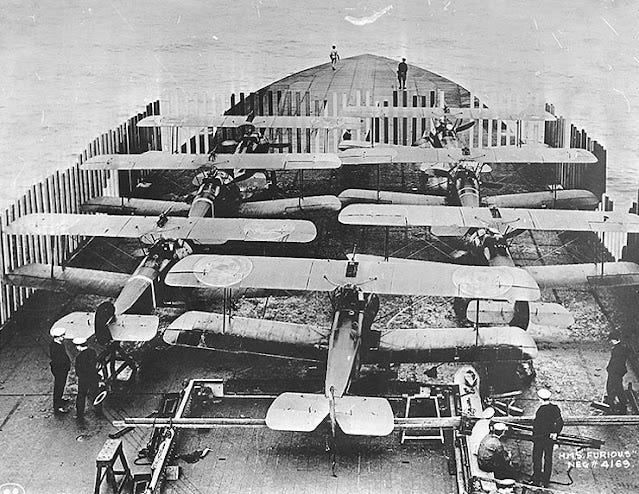

The first airstrike delivered from an aircraft carrier occurred in July 1918 when the Royal Navy’s converted battlecruiser HMS Furious successfully launched seven Sopwith Camels, six of which managed to make it to the Imperial German Navy’s zeppelin base at Tønder, Denmark.

The biplanes dropped their assortment of explosives on the airship hangars, destroying two of them.

None of the planes was able to effect a return landing on the carrier – half put down in Denmark; the other half ditched at sea.

Not a particularly auspicious debut, but it did more or less prove the point that carrier-launched airstrikes were something that could be done.

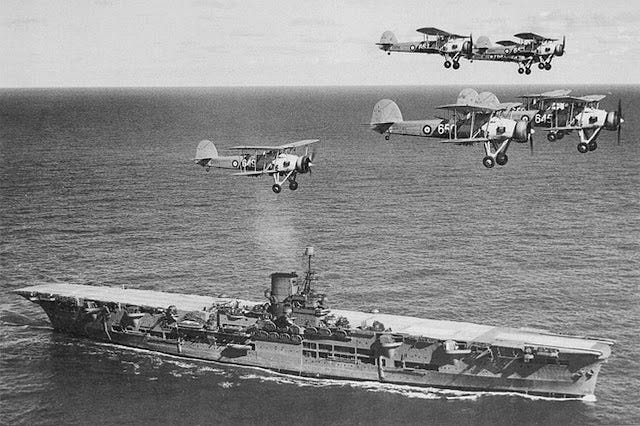

The early 1920s saw the first “purpose-built” aircraft carriers commissioned, by both the Japanese Imperial Navy (Hōshō, 1922) and the Royal Navy (HMS Hermes, 1924).

The United States Navy commissioned the USS Saratoga in 1928, and, as seen below, its silhouette conforms fairly closely to all the carriers that would follow it.

The USS Saratoga carried a complement of 78 aircraft, 2800 crew, a maximum speed of 33 knots, and a range of 10,000 nautical miles cruising at a modest 10 knots.

The Japanese, in 1938, commissioned the modernized “fleet carrier” Akagi, which carried 90 aircraft, could do 31 knots, and had a range of 10,000 nautical miles at 16 knots.

The Royal Navy commissioned its own “fleet carrier” in 1938, the HMS Ark Royal, which carried 60 aircraft, did 31 knots, and had a range of 7500 nautical miles at 20 knots.

Though as yet unproven in battle, these were powerful warships waiting for an opportunity to “show their stuff”.

That opportunity was not long in coming, and in 1941 the age of the aircraft carrier in war commenced, and summarily consigned the battleship to obsolescence.

In May of 1941, the Germans sent their new battleship Bismarck on its maiden mission to raid British shipping in the Atlantic. It lasted all of eight days before being disabled by torpedo attacks from HMS Ark Royal, and was scuttled by its crew to prevent its capture by the Royal Navy.

Of course, the definitive debut of aircraft carrier power was the Japanese attack on the US naval base at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, on December 7, 1941. The Japanese tactics were strongly influenced by the British attack on the Italian fleet at Taranto, and employed shallow-running torpedoes to compensate for the limited depth of the harbor.

The first “blue water” carrier battle occurred in the Coral Sea between the Solomon Islands and Australia in the South Pacific in early May 1942. It was the first sea battle prosecuted entirely via the air wings of the respective carrier task forces.

One month later the famous Battle of Midway occurred, resulting in the devastating loss of four of the Japanese “fleet carriers” – Akagi, Kaga, Soryu, and Hiryu.

These two major sea battles proved the battleship was no longer useful for much besides off-shore bombardment of land installations, and in that sense the age of the aircraft carrier was formally inaugurated.

But, in my judgment, these battles also illustrated the fact that the aircraft carrier, for all its advantages, was acutely vulnerable to airstrikes. Subsequent US success in the War in the Pacific was largely due to its extraordinary capability to produce carriers (and all other types of ships) in historically unprecedented numbers, and to keep them manned with well-trained air crews. After the Battle of Midway, the Japanese were never able to match the Americans in either respect.

That said, the vulnerability of the aircraft carrier to airstrikes never diminished, and even as the Japanese navy shriveled away to a faint shadow of its former self in late 1944, the susceptibility of all surface ships to attacks from the air became more and more apparent.

First Generation “Precision-guided Missiles”

The Battle of Leyte Gulf in October 1944 was a catastrophic defeat for the Imperial Navy, but it also witnessed the initial Japanese experiments with “precision-guided missiles” to attack ships. The guidance systems for these missiles consisted of human pilots who intentionally dove their bomb-laden obsolete aircraft into US ships.

The so-called kamikaze attacks reached their zenith in the spring 1945 Battle of Okinawa, where ~1500 pilots and aircraft were expended, and inflicted substantial damage on large numbers of US warships.

According to a 1999 US Air Force analysis, by the end of the war ~3000 kamikaze sorties resulted in the sinking of 34 US warships and damaged 368 others, with a “hit” ratio of almost 20%.

In my estimation, this is a rather extraordinary success rate when one considers the pronounced disadvantages they faced:

- Kamikaze planes were flown by woefully undertrained Japanese pilots (a great many of them only teenagers) flying what were, by then, even more woefully obsolete aircraft.

- The aircraft typically carried less than about 1000 lbs. of munitions, often in the form of two 200 kg bombs which lacked the explosive punch necessary to do serious damage to a large warship – therefore multiple strikes on the same ship were required.

- The US Navy moved heaven and earth in a substantially inefficacious attempt to prevent the strikes, including massive numbers of aircraft flying combat air patrol out to maximum distances, and many scores of smaller warships deployed in vast arrays of screening ships.

The simple fact was that, despite the highly focused effort to interdict them, US defenses were frequently overwhelmed by large and determined “salvos” of this first generation of precision-guided anti-ship missiles.

Had the Japanese possessed more experienced pilots, and more capable aircraft, outfitted with larger payloads, the toll taken on US aircraft carriers would have been much more severe than it was.

Nevertheless, the kamikaze demonstrated incontrovertibly that warships in general, and aircraft carriers in particular, were – and would continue to be – extremely vulnerable to large salvos of precision-guided munitions.

That vulnerability not only persists to the present day, but is unquestionably more acute than ever before due to the fact that anti-ship missile technologies have advanced much further in the post-World War II era than has the capability of the targeted ships to defeat them.

The US Navy’s Nimitz-class nuclear-powered aircraft carriers are larger than their predecessors and carry more advanced aircraft, but neither they nor the smaller warships that support them are significantly faster nor more maneuverable.

Even more astonishingly, the US Navy’s Order of Battle for the Battle of Okinawa in 1945 consisted of: 11 fleet carriers, 6 light carriers, 22 escort carriers, 8 fast battleships, 10 old battleships, 2 large cruisers, 12 heavy cruisers, 13 light cruisers, 4 anti-aircraft light cruisers, 132 destroyers, and 45 destroyer escorts!

In addition, the Royal Navy provided 5 fleet carriers, 2 battleships, 7 cruisers, and 14 destroyers.

And these were just the combat ships.

Altogether, the fleet arrayed off the shores of Okinawa consisted of over 600 ships!

Nothing even remotely approximating this huge fleet had ever been seen, and quite likely never will be again.

The configuration of current US carrier strike groups consists of a single carrier, 1 guided-missile cruiser, and 3 – 4 destroyers and/or frigates.

So, in a potential battle today between a US carrier strike group and a peer or near-peer adversary, a mere half-dozen ships with an extremely limited number of defenses will face massed salvos of hundreds of cruise missiles, ballistic missiles, supersonic and hypersonic anti-ship missiles, and dozens of submarines with many hundreds of torpedoes – all of which deploy large modern warheads capable of inflicting a mortal blow against any of the ships in the group.

US naval power apologists may argue that the array of defenses on these ships is much more capable than in World War II. But it simply does not matter. It won’t be enough. Regardless of how one attempts to crunch the numbers, a putative engagement between a carrier strike group and the PLA Navy in the South China Sea would entail simultaneous massed attacks of precision-guided anti-ship missiles zooming in from all points of the compass.

It doesn’t require more than middle-school math to realize the inevitable result: the strike group’s defenses would be utterly overwhelmed. In all likelihood, every single ship would be sunk in a matter of minutes. It would be a catastrophic defeat – one which would shock the entire world and forever alter the course of military history.

The plain truth of the matter, in my estimation, is that, faced with the wide array of 21st century anti-ship missiles possessed today by Russia, China, Iran, and likely even North Korea, conventional surface fleets are effectively obsolete, and this will be proven beyond dispute in the first few hours of the next great power war.

Addendum:

A follower on Twitter brought to my attention this instructive simulation of an unintended but rapidly escalated US/China engagement in the South China Sea. While I'm actually inclined to believe the Chinese will perform better and the US worse in such a scenario, the simulation still strongly supports my arguments made above.